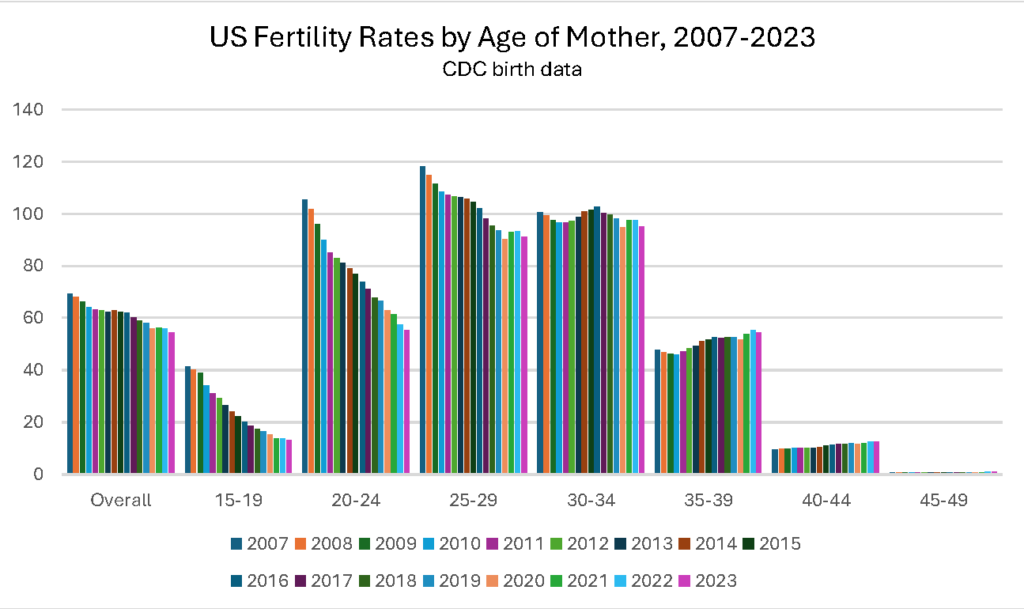

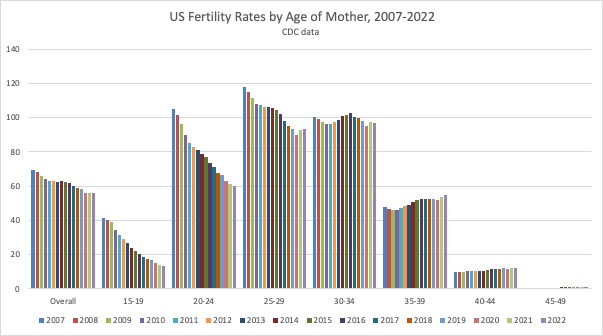

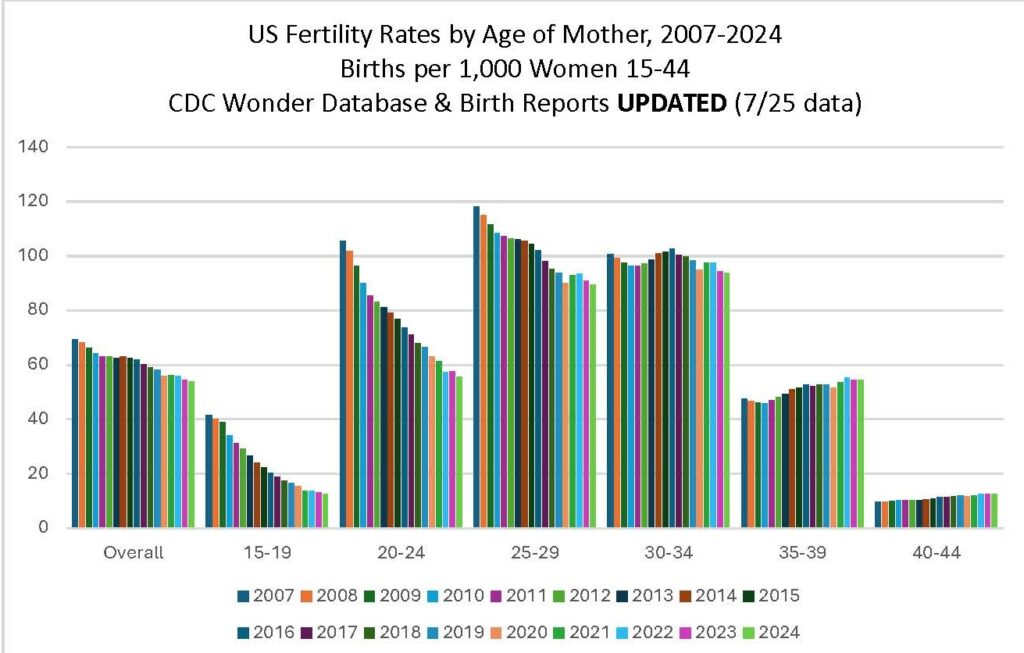

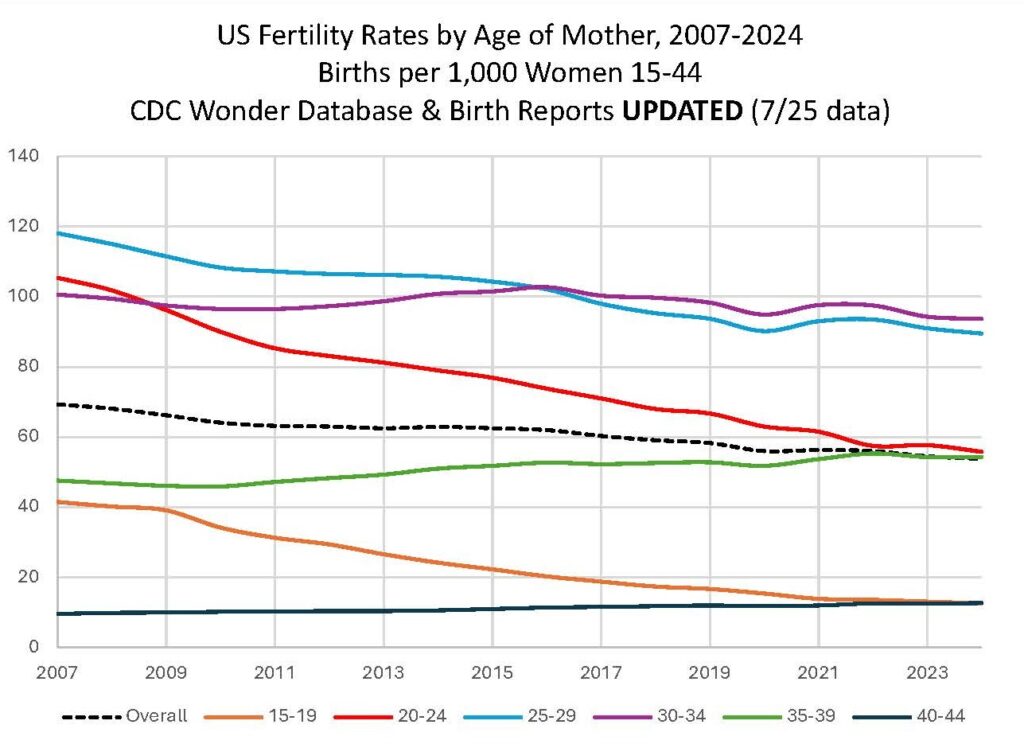

Per updated CDC data, the 2024 Provisional US Fertility Rate fell 1.1% overall (from 54.5 births / 1,000 women aged 15-44 to 53.8) from 2023. That included declines among teens 15-19 (down 4%, from 13.1 to 12.6 per 1,000 women in that age band); among women 20-24 (down 3%, from 57.7 to 55.8); among women 25-29 (down 2%, from 91 to 89.5), and among women 30-34 (down 1%, from 94.3 to 93.7). The fertility rate for women 35-39 as unchanged (at 54.3) while births among women 40-44 rose 2% (from 12.5 to 12.7 births /1,000).

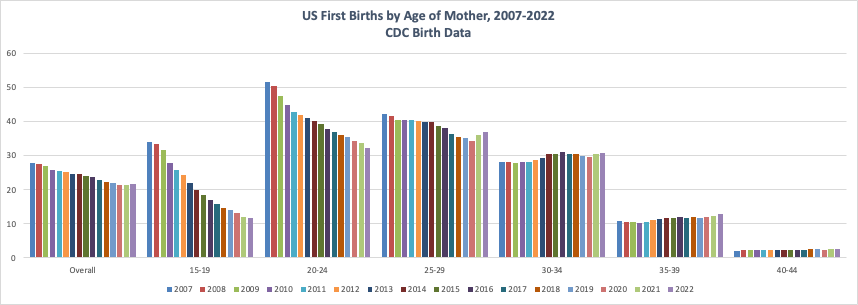

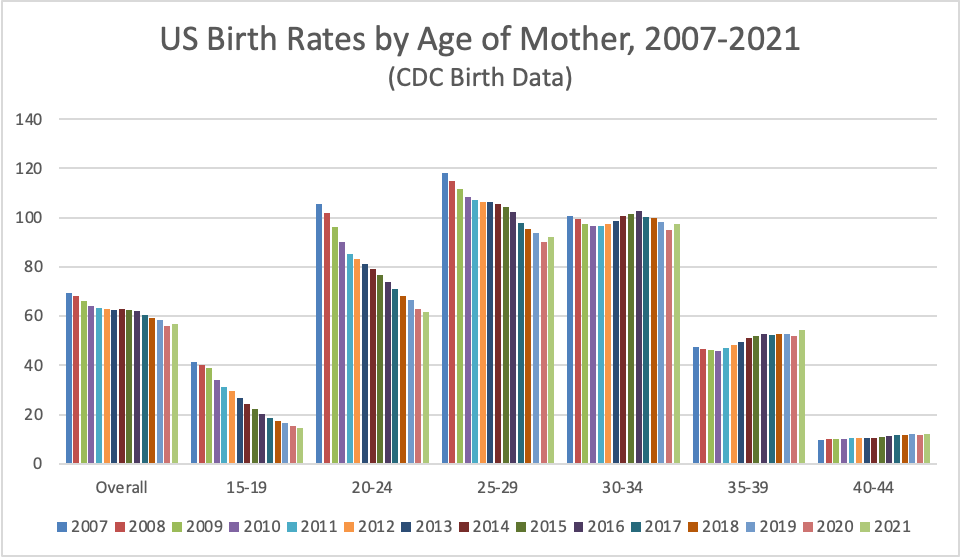

Chart 1 gives perspective on the ripple effect of the changes over time, whereby declining births among teens and women in their 20s since 2007 have to date led to some rate rises among older women (see prior posts for more on this topic). The large numbers of teens who are waiting a beat before starting families (that is, who delay first birth) have led to rising high school and college graduation rates, meaning that when and if they do have children later, they are better able to support them. In 2024, births declined in all age groups except the two highest. The pattern will be more clear once the data on first births becomes available for comparison later this year, so we can tell to what degree the 2024 births among older women are first births and/or additional births.

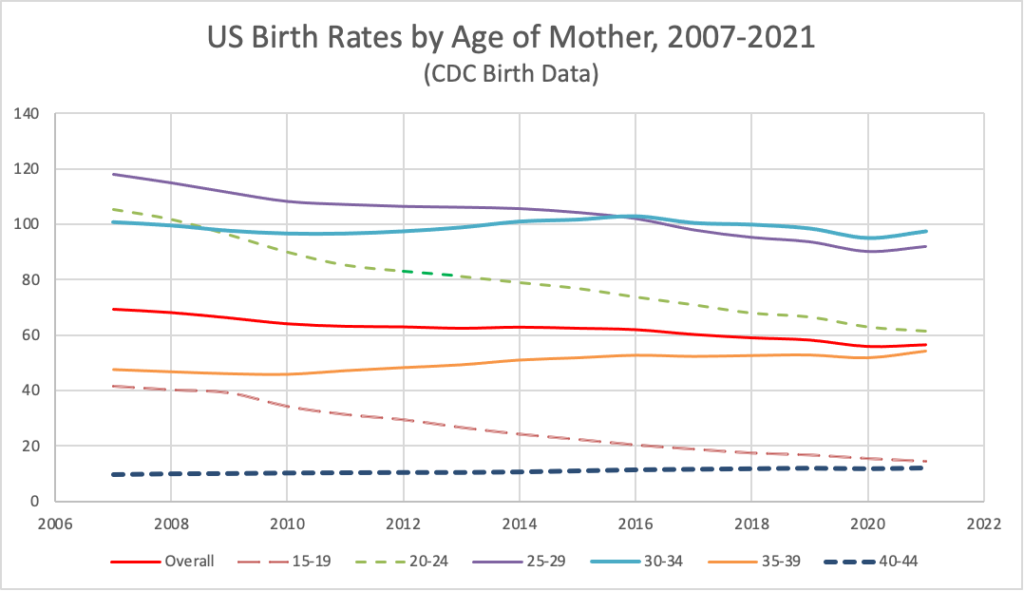

Chart 2 presents the same data linearly, making it visible that the teen rate has now fallen to slightly below that of women 40-44. Similarly, the fertility rate among women 30-34 rose to above that of women 25-29 in 2016, and has remained there, with parallel patterns of rise and fall over the years since. Likewise, the rates for women 35-39 and 20-24 came close to converging in 2024.

The Provisional Reports for 2024 birth data do not include breakouts of the data by state, race/ethnicity, or other factors, so it is not yet possible to compare effects across states or to see who is most affected by the rate changes within and across states. Final birth data for 2024 should be available in September or October 2025.