A recent article in the Atlantic by Jean Twenge on fertility rates among women 35-39 has lots of people talking about later motherhood again. Her data and argument echo a lot of the points I made in Ready, with particular focus on the disconnect between the data cited in the many tick-tock media stories on fertility decline after 35, and the reality that most women have kids with no problem in the 35-39 age band.

A recent article in the Atlantic by Jean Twenge on fertility rates among women 35-39 has lots of people talking about later motherhood again. Her data and argument echo a lot of the points I made in Ready, with particular focus on the disconnect between the data cited in the many tick-tock media stories on fertility decline after 35, and the reality that most women have kids with no problem in the 35-39 age band.

Here’s her good data summary:

One study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology in 2004 and headed by David Dunson (now of Duke University), examined the chances of pregnancy among 770 European women. It found that with sex at least twice a week, 82 percent of 35-to-39-year-old women conceive within a year, compared with 86 percent of 27-to-34-year-olds. (The fertility of women in their late 20s and early 30s was almost identical—news in and of itself.) Another study, released this March in Fertility and Sterility and led by Kenneth Rothman of Boston University, followed 2,820 Danish women as they tried to get pregnant. Among women having sex during their fertile times, 78 percent of 35-to-40-year-olds got pregnant within a year, compared with 84 percent of 20-to-34-year-olds. A study headed by Anne Steiner, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, the results of which were presented in June, found that among 38- and 39-year-olds who had been pregnant before, 80 percent of white women of normal weight got pregnant naturally within six months (although that percentage was lower among other races and among the overweight). “In our data, we’re not seeing huge drops until age 40,” she told me.

The new 2013 data from Rothman and Steiner supports Dunson’s data, which was also much more in line with my own experience and the experience of women I knew and interviewed. Here’s my discussion of Dunson’s “European Fecundability” data in Ready:

If you’re 35, you’re probably fertile: A study from the 1950s indicated that, while 11 percent of women could have no babies after 34, the rate rose to 33 percent after 39, and 50 percent after 41. Though this data may not accurately reflect the current fertility scene, no more reliable data for women 35 to 50 is available today. Some recent results do corroborate the general trend of the 1950s study for women 35 to 39, however. Data collected at seven European natural family-planning centers in the late 1990s (the European Fecundability Study) indicate that about 90 percent of women not already known to be infertile due to pre-existent issues like endocrinal disorders or surgery who try to conceive between ages 35 and 39 will become pregnant within two years. That’s if they use natural family-planning methods (charting temperature and cervical mucous to more accurately predict when ovulation happens and to shorten time to conception) and have sex at least two days per week. [1] Roughly 82 percent will become pregnant within one year.[2] (From Ready, chapter 6 “Sarah Laughed: Who’s Fertile & How”)

The natural family-planning info echoes Toni Weschler’s fertility awareness method in Taking Charge of Your Fertility and the Creighton Method, used for both avoiding and finding fertile times, and endorsed by the Catholic Church.

Important to note that becoming pregnant is not the same as carrying to term, and that miscarriage rates of established pregnancies (not in the first few days) among women in their late 30s and 40s occur at higher rates than among younger women (Twenge cites a figure of 26% for women 35-39, and another study indicates a rate of 30% among women over 40).

Even including these qualifiers, 35-39 fertility rates are much higher than those indicated in Sylvia Hewlett’s Creating a Life, which cited “the Mayo Clinic,” without any further documentation, claiming

“Fertility drops 20 percent after age 30, 50 percent after age 35, and 95 percent after age 40. While 72 percent of 28-year-old women get pregnant after trying for a year, only 24 percent of 38-year-olds do.” (pp. 216-17).

Completely untrue. But this kind of “data,” along with anecdotal stories from women who haven’t gotten pregnant when they wanted to–not to be ignored but which give you no sense of the big picture–have filled our narrative about fertility ever since (see Ready 2012 for more on fertility scaremongering).

Twenge joins me in wondering why such too-low or otherwise distorted data are allowed to appear unquestioned on so many fertility sites and reports. Certainly anxiety generates profits for doctors and media, and there may be an unwillingness among media reps about overstating fertility, so that people understand that waiting does not work out for everybody (I ran into some of that with Ready).

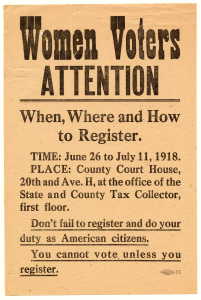

These reports also feed into the fierce political debate about fertility, birth control, and abortion going on across the nation, by problematizing later fertility inaccurately–as well as the decision to have no children that some women may be comfortable with, but which becomes more difficult to articulate in a context focused on the misery of infertility. No question that fertility does decline, but give women the facts, and they can figure out how that fits with their own sense of what’s important for them and when.

Overstating infertility also carries risks for women and their families. One woman I spoke with figured it was time to get busy when she heard a news report on how a woman’s “loses 90% of her eggs by 30,” even though she and her new husband had planned to wait a few years to establish in their jobs and their relationship. Given the story, she figured it would take a while. A year later she was working freelance from home with baby, unable to afford good care otherwise, and not happy with the situation that had sidelined her career. (College Grads See Big Wage Gains from Delay)

On the other hand, in spite of the tick-tock narrative, many women have figured out for themselves, by observation of people around them and deduction, that delay is possible and that it makes sense for them.

Thus in 2011, with the birth rate at an all-time low, the only age group in which births rose was women 40-44. While birth rates among women 15-24 fell markedly in 2011, and rates to women 25-29 fell 1%, rates among women 30-34 held steady, and rates rose 3% among women 35-39, 1% among women 40-44, and held steady among women 45+. One in 12 first babies had a mom 35+ in 2011, as did 1 in 6.8 overall. 580,357 babies were born to women 35 and over in 2011, including 463,849 to women 35-39, 108,920 to women 40-44, 7,025 among those 45-49 and 585 to women 50 or more.

The low birth rate held steady in 2012, with break outs by age, race and other factors due out in November.

May the fertile discussion continue!

[1] Bernardo Colombo and Guido Masarotto, “Daily Fecundability: First Results from a New Data Base,” Demographic Research 3 (2000): article 5; David Dunson, Bernardo Colombo and Donna Baird, “Changes with Age in the Level and Duration of Fertility in the Menstrual Cycle.” Human Reproduction 17 (2002): 1399-1403; David Dunson, Donna Baird, and Bernardo Colombo, “Increased Infertility with Age in Men and Women,” Obstetrics and Gynecology, 103 (2004): 57-62; Bruno Scarpa, David Dunson, and Bernardo Colombo, “Cervical Mucus Secretions on the Day of Intercourse: An Accurate Marker of Highly Fertile Days.” European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 125 (2006): 72-78.

[2] This study estimates infertility (the diagnosis if a couple has been trying consistently to conceive for a year without success) at 8 percent for women aged 19 to 26, 13-14 percent for women aged 27 to 34 and 18 percent for women aged 35 to 39. (The study didn’t look at women over 40.)

In celebration of Labor Day, here’s a blast from the past on this blog.

In celebration of Labor Day, here’s a blast from the past on this blog.

The NY Times‘

The NY Times‘

For egg freezing, a new procedure, there’s limited success rate data available because few of those who’ve frozen their eggs have come back to have them fertilized and implanted, but here’s a link to an info and advocacy website called

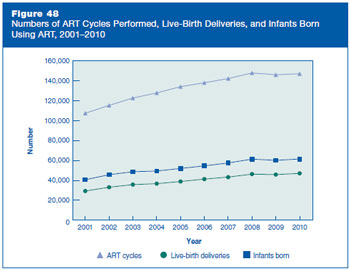

For egg freezing, a new procedure, there’s limited success rate data available because few of those who’ve frozen their eggs have come back to have them fertilized and implanted, but here’s a link to an info and advocacy website called  While the success rates for these technologies have improved over time overall, especially for younger women, the numbers of attempts and of births declined between 2008 and 2009, along with the total number of US births, but have resumed their rise since then. (

While the success rates for these technologies have improved over time overall, especially for younger women, the numbers of attempts and of births declined between 2008 and 2009, along with the total number of US births, but have resumed their rise since then. ( A recent article in the Atlantic by

A recent article in the Atlantic by